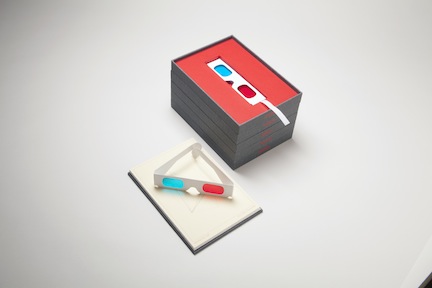

One for Each (2012)

$550.00 :: CLICK TO PURCHASE

Paolo Salvagione has created a sensory Wunderkammer. His elegant cabinet of curiosities contains five drawers, one for each of the human senses. Each drawer holds a distinct, self-contained object; three-dimensional visuals emphasize the tactile nature of printed images. Silhouettes of leaves ask you to gauge species by contour, yet the absence of color brings attention to the visual. Talking tapes acknowledge a tangible aspect of sound. A musky, smell-based exploration summons up mental images of physical activity. A unique taste enhancer promises to temporarily bond to your receptors, making all things sour seem sweet — but first, your fingers must negotiate the brittle blister pack. Overall, the work seeks to show readers/viewers how our senses often deceive us and, in the process, yield something akin to a child's surprise at the roles these senses play in helping us navigate the world.

Salvagione has enlisted Boon Design to oversee typography, and Marc Weidenbaum to develop a series of short interlocking essays.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Paolo Salvagione is an artist who works at the intersection of engineering, participation, and levity. He was born in Chicago and at an early age moved with his family to Southern France, where he developed an affection for bullfighting. He spent his teen years in Albuquerque, New Mexico, living around the corner from Joel-Peter Witkin, whom he occasionally assisted with set construction and corpse transportation. He spent his college years in Manhattan reading philosophy. Grounded in the practice of thinking about thinking about things, he spent a half a decade circling the world setting up bicycle factories from Italy to Indonesia — mastering titanium fabrication after hours at Martin Marietta in Colorado, working on next-generation paint-application systems for Boeing, employing CAD software for hi-tech bike design in Marin, even designing an atmospheric-dust collection tool for NASA. And he has worked, for over a decade, as lead engineer on the 10000 Year Clock of the Long Now Foundation.

In his art, Salvagione has sent his studio visitors out one second-story window and in another on a 900-pound steel wheel. He has used a laser cutter to give negative space a razor-sharp edge, creating a frozen bellows of light. He has filled a World War I gymnasium with a mix of pure geometry and pure fun in the form of ten oversized swings, with the implicit suggestion that visitors compete. He has commented on the role of finance in the art market by selling uncut currency presented in a fetishized box, including a pair of paper sheers. And he has pushed kinetic sculpture past what the eye perceives as sufficiently balanced.